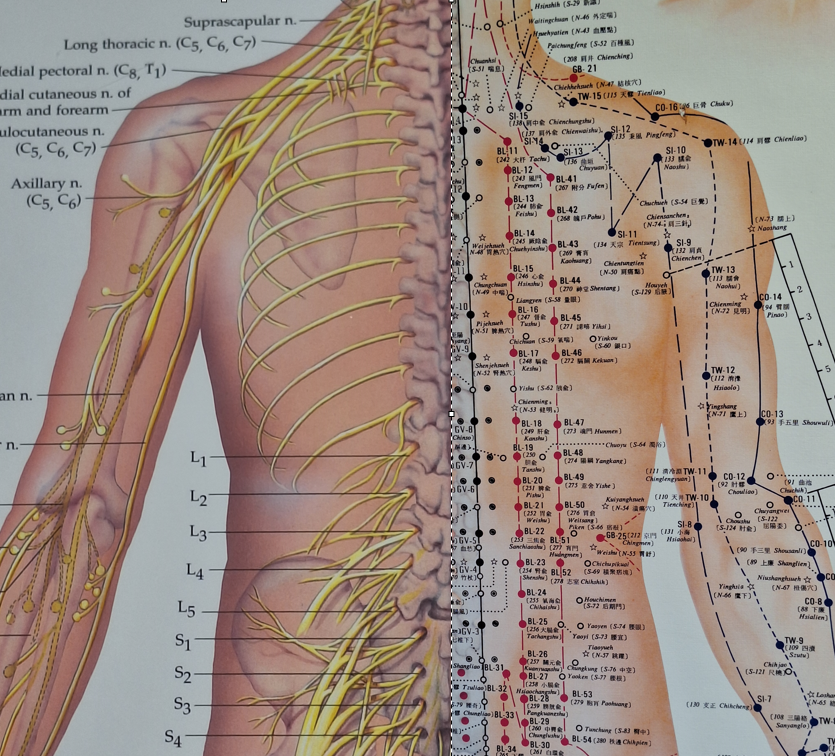

Spinal Nerves (Left) Versus Meridians (Right)

If there is one thing that is said to me, over and over again, it is: “I don’t like needles.” If there is another thing that is said to me over and over (and over) again, it is: “How does acupuncture work, scientifically?” In clinic, I endeavor to answer this question, but because time is limited and the subject is complex, I feel there is rarely, if ever, a successful understanding of this topic created. So, after many, many years, I decided to give this question the answer it deserves.

If you have had acupuncture before, at some point you probably noticed your acupuncturist had colorful charts on the wall depicting the classical acupuncture point locations. These points are linked one to another by a series of lines called “meridians,” or channels. In Traditional Chinese Medicine thinking, these lines represent an energetic connection between points.

According to traditional theory, your body’s vital energy, or “qi” flows along these lines. If your state of health is good, the qi flows smoothly. If qi is blocked by trauma, stress, poor diet, or environmental factors, it slows, or stagnates, resulting in symptoms. It is considered the job of the acupuncturist to locate these blockages and remove them by stimulating the acupuncture points, usually with needles.

Many people will accept this conception. Intuitively, it makes sense, and it resonates with the metaphor of waterways or traffic flows. However, some people will balk as they consider this explanation to be unscientific. And truth be told, they are correct! In our western scientific paradigm, there are various units for measurement of different types of energy. If qi is a form of energy, there should be a way to measure it. There is none.

Do the acupuncture points and meridians represent nodes of energy and connections in between them? In my opinion, no. Certainly, these points have significance, which I will explore below, but the science of energy is physics, and the sine qua non of physics is measurement, and qi cannot be measured. Which is not to say there is no energy flow in the body, in fact there is constant movement of thermal, chemical, and electrical energy. One way to explain Qi may be to consider it an aggregate of these processes. However, there is no singular defining characteristic of what qi is relative to other forms of energy.

How were these points discovered? It is unclear, lost in the haze of the past. It is certainly possible that the ancient Chinese mapped these points empirically, through palpation and trial and error. Perhaps they realized the physiological significance and treatment utility of stimulating these points, but did not fully understand the mechanism of action. It is possible they crafted a system of explanatory value that was internally consistent and useful, but does not correspond to modern anatomical understanding. I believe this is the case.

But the question remains: if the acupuncture points are not conduits for qi energy, then what are they? And why does it matter? It is still possible to utilize the meridian system for diagnosis and treatment, and many Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) trained acupuncturists do. However, there are several problems with this approach. One, the terminology of TCM alienates western trained healthcare professionals. This is why the concept of “dry-needling” has been so successful. By retaining the techniques of acupuncture and repackaging the conceptual framework, it is much more palatable to the medical community. (As an aside, It is somewhat bittersweet to me after many years of having my treatment rejected by science minded individuals, to watch it become enthusiastically embraced by the physical therapy community as the newest and hottest method around. There is a lesson for myself and my profession here, but that’s for another time).

The second limitation is that it limits refinement and growth. Traditional Chinese Medicine is a canonical medicine, meaning it is based on the classics. Characteristics of acupuncture points are handed down as “statements of fact,” immutable axioms. On the one hand, there is a high degree of value in this, as the past represents a rich store of knowledge. On the other hand, it can inhibit new approaches. New discoveries in anatomy and physiology can form the basis for new techniques, and they often are. For example, scalp acupuncture based on fMRI of brain activity has become quite popular. This approach has little reference to the classical acupuncture paradigm. Of course, dry needling replicates acupuncture techniques with no incorporation of meridian concepts whatsoever. The success of these methods call into question the relevance of the traditional conceptual framework.

We still have not answered the question of what the acupuncture points are. Various explanations have been proposed. In the dry needling community, it is largely (but not completely) accepted that they are myofascial trigger points. Myofascial trigger points represent areas within muscles that are prone to fatigue and accumulation of metabolic waste. They are tender to palpation and often will radiate pain in a predictable pattern when pressed. These patterns often correspond to acupuncture meridians. The myofascial trigger points as mapped out by Dr. Janet Travell do indeed have a high degree of correspondence with the acupuncture points.

Other people such as Dr Helene Langevin have proposed that the acupuncture meridians represent fascial planes. Some acupuncturists have latched on to more obscure concepts, such as “Bonghan ducts.”

It is beyond the scope of this article to detail the pros and cons of each of these approaches. However, in my opinion, the most likely and most obvious explanation is that the acupuncture points represent nothing other than areas of neuroanatomical significance.

I first noticed this many years ago when comparing a chart of the peripheral nervous system side by side with an acupuncture point chart. The meridians were too close to the nerves to be coincidental, yet at the same time they were not completely aligned. My opinion was confirmed when I started studying the work of Dr. Poney Chiang. According to Dr. Chiang, research to investigate the anatomical significance of acupoints systematically began in 1959 at the Shanghai First Medical College. Their research showed that the acupuncture points have a very high degree of coincidence with areas of neuroanatomical relevance.

For example, 323 of 324 acupoints are associated with peripheral nerves. 93.83% are associated with superficial cutaneous nerves, and 52.5% are associated with deep nerve trunks. Additionally, in experiments, using nerve anesthetic techniques removed the effectiveness of acupuncture points, suggesting that their function is based on neurology, not on unseen energy circulation.

What are the implications of this? It means that the acupuncture points are nothing other than areas to access the nervous system for stimulation, and that the needles (combined with electrical current), are a vector for achieving that stimulation. It also means that optimization of the acupuncture treatment requires a thorough understanding of the nervous system.

The nervous system is divided into the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), and the peripheral (nerves extending from the spine into the limbs). The three types of nerves are sensory, which provide

sensation, motor, which activate muscles, and autonomic, which are further divided into sympathetic and parasympathetic, which have various stimulating or sedating effects on the organs, circulation, glandular secretion, etc. What the meridian system gives us, when properly interpreted, is nothing less than a road map to normalizing various functions within the nervous system. Through this system, you can modulate pain, but also remove motor inhibition (increase movement), and normalize autonomic (organ) function.

Think of how remarkable this really is!

What does this mean for you? Most acupuncturists have some familiarity with this concept, but many remain in the traditional paradigm. Some utilize this framework, but very few explore the depths of neuroanatomy this approach necessitates. To get good results with this methodology requires a commitment of constant study and research. It requires a rigorous clarity of diagnosis and a specificity of technique.

In my opinion, however, it is worth it. Using a neurologically based approach to acupuncture produces an accuracy in results not obtainable with traditional thinking. As well, allows integration by using the common vocabulary and concepts of biomedicine. (Sometimes I am a little saddened when I think of all the people I’ve met who rejected acupuncture because they believed it had no scientific basis.) Finally, it opens the door to innovation, allowing research from other modalities, such as clinical neurodynamics, anesthesiology, and electromedicine to be seamlessly integrated into acupuncture practice. This can do nothing but benefit our patients.

For me personally, this does not erase the TCM meaning of the point, rather it enhances it. Hopefully, you now have some deeper understanding of what acupuncture is. In future articles, I will explore the actual mechanisms of action of needling with electricity and how it can be used to benefit you.

TLDR: Acupuncture points and meridians are really nerves, and acupuncture stimulates nerves to relieve pain and improve function.